Diversion program to help North Side teens, shows early promise

About three months ago, a group of 13- to 16-year-olds who caught the school bus at East Ohio Street and Cedar Avenue on the North Side noticed that the door of the Subway sandwich shop had a broken lock—so they went in and took some chips to munch on while they waited. They did it again the next day. The third day, they did it again, and were arrested—and charged with burglary, a felony.

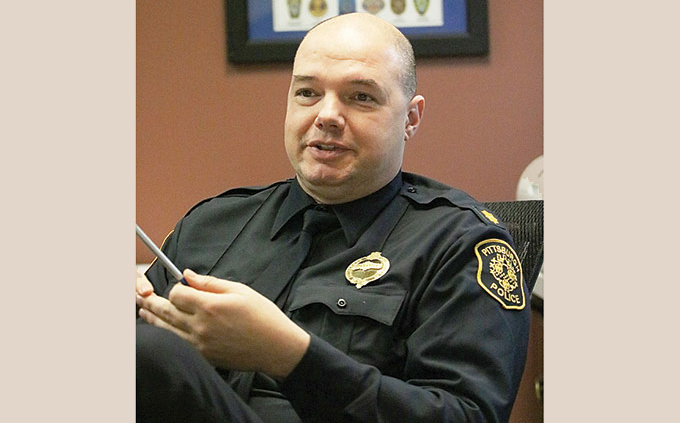

“We bring them in and learn they aren’t hardened criminals, they’re just kids who knew better but probably didn’t know the gravity of the situation. So we worked with juvenile court to put them in the program” -CHRIS RAGLAND, Zone 1 Police Commander

Before, that felony arrest could have stayed on their record, following them for life, limiting or crippling their chances for success. But thanks to the pilot North Side Diversion Program, those kids can get those charges erased. And Zone 1 police Comdr. Chris Ragland and his officers are glad to be able to take advantage of it.

“We bring them in and learn they aren’t hardened criminals, they’re just kids who knew better but probably didn’t know the gravity of the situation. So we worked with juvenile court to put them in the program,” Ragland said. “There are times in life that are a tipping point; if we can interject at that time, perhaps we can prevent that person’s life from going on a downward spiral.”

“We need to market to the community. We want them to know police are there to serve—not just arrest and incarcerate.”

SYLVESTER WRIGHT, Pittsburgh Police Officer

The program first started in 2016, but was shut down when one of the original partners had to drop out. It started back up in May under the direction of Jeff Williams and is housed at the Foundation of Hope. It is funded by grants from the Buhl Foundation, the Pittsburgh Foundation and the Dollar Bank Foundation, and, in addition to the Pittsburgh police, it takes referrals from the Allegheny County Juvenile Probation office and the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh.

It was initially conceived as a means to offer an alternative to incarceration for individuals aged 13-26 charged with minor, non-violent offenses, but has evolved into a more proactive program.

As Ragland and Williams noted, with minor offenses that would typically be pleaded down to a summary offense with a fine, there was no real incentive to change behavior. Now, officers refer individuals in a broader range of situations—and they are getting services not just to the kids, but to their families, as well.

Pittsburgh Police Officer, Sylvester Wright

“We had a 12-year-old kid caught with 70 stamp bags of heroin—that’s a serious charge,” said Zone 1 officer Darrick Payton. “In the past there was no hope for that kid. But the DA, to his credit—especially with the opioid crisis—OK’d him for the program. We have a lot of people on the same page, their minds and hearts in the right place and so is the money. We have the time and the money to do this. People recognize we all have a vested interest in successful children.”

Williams said there is no longer a published set of “divertable offenses.” Referrals are determined on a case-by-case basis—a kid who stole a bicycle, another one who was hanging out at a gas station soliciting customers for spare change, or odd jobs when he should have been in school.

“He hadn’t committed a crime yet, and it took us from October to get his mother to sign off on getting him in the program,” said Williams. “I hadn’t even gotten a plan together for him yet. So I’m following up and I find out he’s in (the Shuman Juvenile Detention Center). Apparently, he tried to steal an iPhone from the store in South Hills Village—how he got there, I don’t know. I’m going to court with him later this morning.”

Pittsburgh Police Officer, Darrick Payton (Photos by J.L. Martello)

The community is slowly buying into the program as Ragland, his officers, and Williams get the word out. As long as the offense isn’t violent, even a first-time offender charged with possession with intent—like the 12-year-old—might be eligible. So might a kid charged with possession of a gun.

“Now the DA hasn’t signed off on that, but there could be a situation where a kid is holding a gun for someone, or he got one on the street for protection but has never used it and has no record,” said Ragland. “If we can show that we can maybe get a felony charge dismissed if a kid cooperates—that gets us a lot of credibility with the community, and is a big leap in people coming on board.”

Officer Sylvester Wright, a 23-year veteran and Payton’s partner, said getting the families involved is critical, and this program can help build the relationships that make that happen.

“The biggest benefit is when we meet these kids and say we want to help, they can see that we aren’t running some kind of game on them,” he said. “They begin to trust us and we can establish those relationships. “Helping is something they don’t see. This program is designed to help.”

Williams said he is optimistic about the program’s future.

“It’s still in its infancy. We’re looking to see who we need to serve, we have the referral process down, and we know how to get resources to people,” he said. “We need to market to the community. We want them to know police are there to serve—not just arrest and incarcerate.”

Originally published on March 11, 2018

SOURCE: New Pittsburgh Courier